1 Chapter 1- Introduction to the Study of Adolescence

A Multidisciplinary Exploration

Gowri Parameswaran

Learning Goals

- Comprehend the biological and psychological frameworks used to understand adolescence

- Learn about the historical framework for understanding adolescence

- Explore the postmodernist critique of social constructions of adolescence

- Explore how social location affects adolescence

- Understand the differences and similarities in the frameworks used to understand youth lives

Chapter Outline

- The Teenage Mystique: Neither Child nor Adult

- Raging Hormones: A Biological View

- Problems with Brain Analysis

- The Psychological Perspective

- The Psychoanalysts

- Cognitive View

- Ecological Theories

- Recent Critical Perspectives

- Historical Framework

- Sociological Perspective

- Aesthetic-Literary View

- Emancipation Theories

- Postmodernist Critique

- Political Perspective

- Conclusion

- Glossary of Terms

- References

The Teenage Mystique: Neither Child nor Adult

My ancestors were Tamil Brahmins from a small town in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. We belonged to the highest caste in a very unequal and rigid social system. Although caste discrimination was officially banned after India gained independence, traditions like child marriage continued in rural areas for a long time. My grandmother was married at just 8 years old and had her first child at 13. My grandfather was only 16 when they married. Together, they raised six children, five of them daughters. My eldest aunt was married at 13 and became a mother at 14. In contrast, my mother was married by arrangement at what was then considered the “old” age of 21. One generation later, my sister and I didn’t marry until our late twenties and early thirties, and we chose our own partners. We both pursued higher education and focused on building our careers. My children, now grown men, were raised in the U.S. and had a fairly typical American adolescence. Still, as second-generation immigrants, they had to learn to move between two cultures—South Asian and American. I share this story to show how much the lives of young people between the ages of 13 and 18 can differ across time, place, and culture.

Many people, especially in popular media and everyday conversations believe that adolescence is mostly shaped by biological changes. However, among scholars, there has long been debate about what adolescence really is and where it comes from. This chapter introduces several key ways researchers and thinkers have tried to understand adolescence. These include: (a) biological and psychological approaches, (b) ecological frameworks, (c) poststructuralist and postmodernist theories, (d) historical perspectives, (e) sociological analyses, and (f) literary interpretations. Each of these frameworks will be explained in detail, along with the kinds of evidence used to support their claims. Where relevant, we’ll also highlight gaps in our current understanding. As you’ll see, the ideas in each school of thought are not fixed; they continue to evolve and spark discussion.

In today’s industrialized societies, the average girl reaches puberty around age 12.5. Just a couple of hundred years ago, it was closer to 16 (Chumlea et al., 2003; Evelith, 2017). While the age of sexual maturity has been falling, the average age at which women have their first child has been rising; it’s now just over 26 in many developed countries. This growing gap between physical maturity and starting a family is largely due to modern economic demands. In today’s global economy, young people often need many years of education and training before they can think about settling down (Whelpton, Campbell & Patterson, 2015).

The concept of “adolescence” itself is relatively new. Historians trace its origins to the early 1800s, during the rise of industrial society. The term first became widely known through the work of psychologist G. Stanley Hall in the early 20th century (1904; 1916). His influential books helped launch the field of adolescent studies. At the same time, the spread of European empires and the rise of scientific thinking pushed societies to classify people in new ways, by age, gender, race, class, and place of origin. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution gave these efforts a powerful framework. He argued that life evolved in a single direction: from simple to complex, from less specialized to more differentiated. This idea supported the belief that societies, and even individuals, could be ranked by how “evolved” or “advanced” they were, which had lasting effects on how adolescence and other life stages were understood.

Early thinkers who studied human development borrowed ideas from Darwin, but in a simplified way. They believed that life forms that appeared later in history were better suited to survive than earlier ones (Charlesworth, 1992; Morss, 2017). These early scholars drew comparisons between how species evolve over time and how human societies developed through history. Those who used Darwin’s ideas to explain social change were called social Darwinists. They argued that early human societies were simple and, over time, became more complex, eventually leading to modern industrial societies. For example, they saw hunter-gatherer groups as less advanced than farming communities, and farming societies as less developed than industrialized Western nations (Paul, 2003). Social Darwinists also applied this thinking to individual human development. They saw a person’s life as moving from a simple stage in childhood, through a more complex phase in adolescence, to full maturity in adulthood. In this view, adolescence became an important turning point, a stage where young people were expected to make decisions that would shape the kind of adults they would become (Arnett, 1999).

According to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, adolescence is the period of transition between childhood and adulthood. While this definition sounds straightforward, experts from different fields have debated what it really means. Many theorists, philosophers, and cultural critics, especially in sociology, history, and postmodern studies, argue that adolescence is not just a natural stage of life. Instead, they believe it is a social construct, something shaped by culture, history, and society rather than biology alone.

On the other side of the debate, many researchers in biology and psychology believe that adolescent behavior is largely shaped by real biological changes, such as shifts in hormone levels and brain development. Whether a researcher sees adolescence as a social construct or a biological fact has a big impact on the kind of research they do, and the policies they recommend. Before we begin to explore adolescence in depth, it’s important to understand the reasoning behind these different perspectives and the kinds of evidence each one uses to support its claims.

Raging Hormones: A Biological View

Most mainstream psychologists agree that puberty marks a major turning point in a person’s development. In the U.S., biological sexual maturity usually begins around age 12.5 for individuals assigned female at birth (AFAB) and around age 14 for those assigned male at birth (AMAB). A key sign of puberty in AMAB individuals is the first ejaculation, while in AFAB individuals it is menarche, or the first menstrual period (Evelith, 2017). Biologists explain that the physical changes of adolescence are largely driven by a surge in sex hormones, triggered by increased activity in the hypothalamus. In AFAB individuals, the ovaries release two main hormones: estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen is responsible for changes like breast development and the functioning of the uterus and vagina. Progesterone helps regulate the menstrual cycle and prepares the uterus for pregnancy. In AMAB individuals, the testes produce androgens, mainly testosterone, which drives the development of male sexual characteristics and supports the function of male reproductive organs. It’s important to note that both estrogen and testosterone are present in all developing bodies, just in different amounts depending on biological sex.

The discovery of these biological changes has led many experts to describe adolescence as a time when impulses often take over teen behavior.

Brain Imaging and Teen Behavior

In recent years, advances in brain imaging, especially functional MRI (fMRI), which allows scientists to take “live” pictures of brain activity, have helped researchers learn more about how the adolescent brain develops. One widely accepted idea among brain scientists is called the dual systems model. According to this theory, the parts of the brain involved in emotions and social rewards develop faster during adolescence than the parts responsible for careful, long-term thinking. As a result, teens may be more likely to seek out rewards and focus on success, while underestimating risks or the chances of failure (Steinberg, 2010; Goodenough & Freeman, 2017). The area of the brain responsible for planning and decision-making is the prefrontal cortex, located at the front of the brain, which develops more slowly. This part is essential for goal-setting, self-control, and problem-solving, and is often seen as what makes human thinking distinct. Picture: Dual systems model

There has been some criticism leveled at this model in studies that show that teens tend to engage in risky behavior more often when their peers are around. So, the capacity to engage in risky behavior may be a regulated action in order to win approval or admiration by their friends. In addition, adults can behave in risky ways as well; for instance, when speculating on risky stocks that have a higher than average rate of tanking but might have quick short-term gains, adults exhibit a similar propensity as adolescents.

Brain researchers explain youth behavior with something called neural pruning. This means the brain gets rid of connections between brain cells (neurons) that aren’t used much, and makes stronger connections for thinking better and connecting different parts of the brain. During the adolescent years, the front part of the brain (called the prefrontal cortex), which helps with planning and making decisions, loses about half of its connections. At the same time, important pathways get stronger. Some scientists think this rapid brain change can make how teens think less steady. Youth start to think in more complicated ways, which brings new and sometimes confusing feelings and ideas. Because of this, youth might act in ways adults don’t always understand (Siegel, 2015). Picture: Neural pruning at 3 ages – 1, 8, 13

Researchers say another important brain change happens in areas that make chemicals like dopamine and serotonin. These chemicals affect mood and behavior. A gene on the X chromosome makes a protein that lowers dopamine and serotonin levels. Since boys have only one X chromosome, any problems with this gene show up more strongly in them. This can lead to behaviors like starting drug use early and having trouble controlling impulses. During the adolescent years, brain circuits that use dopamine become more active, making teens want more excitement and adventure. Because of this, thrilling experiences can feel addictive, providing a powerful rush of the pleasure hormone, dopamine. Thus, negative outcomes are undervalued in their rush to seek new experiences and excitement (Casey, 2015; Janssens et al., 2015).

Similarly, scientists think that having too little serotonin, a brain chemical, can affect mood, lead to impulsive actions, and make people take more risks. In adults, low serotonin levels have been linked to depression and emotional imbalance. But in teenagers, researchers say it’s more about the balance between two chemicals: serotonin and dopamine. Serotonin levels are highest in childhood, but the system that controls dopamine is still developing during the teen years. This means teens have a harder time managing their emotions, while also wanting more excitement and rewards, which can lead them to take more risks (Walker et al., 2017).

Brain scans have been used to show that there are real biological differences between adults and teenagers (Somerville, 2016). In one common experiment, researchers showed pictures of faces with different emotions to both teens and adults while watching how their brains reacted. Some studies found big differences in which parts of the brain were active, while others didn’t. In one study, most teens saw a scared face and thought it was angry, while most adults saw the emotional expression on the face as fear. The researcher explained this by saying teens were using the older, emotional parts of the brain, while adults were using the front part of the brain that helps with thinking and judgment. Based on this and other studies, scientists believe teens may be less logical when reading emotions, which can cause misunderstandings with adults (Crone & Elzinga, 2015; Silveri & Sneider, 2014).

In short, a common idea in research about the teenage brain is that teens go through major changes in their bodies before their brains are fully developed. Their sexual hormones are fully active by the teen years, but the part of the brain that helps with decision-making and self-control, the prefrontal cortex keeps growing into their twenties. Because of this, teens are often seen as having adult desires but child-like emotions. Brain scientists say teens may feel ready for sex and independence, but they still need support from adults to handle these things responsibly. They enjoy excitement and new experiences, but they often struggle to set limits and think things through carefully.

Problems with Brain Analysis

Problems with Using Brain Scans to Make Generalizations About Age-Related Changes

-

Brain scans show patterns, not causes: Brain scans can tell us which parts of the brain are active, but they can’t tell us exactly why someone acts a certain way. Just because a teen’s brain looks different doesn’t mean that’s the reason they take risks or feel strong emotions.

-

People develop at different rates: Not all teens or adults are the same. Some teens may develop certain brain areas earlier or later than others. So it’s not accurate to make big claims about all teens based on average brain scan results.

-

Behavior is shaped by more than the brain: Things like family life, culture, school, and personal experiences all influence how people think and act. Looking only at brain scans leaves out these important factors.

-

Brain scans have limits: Brain imaging tools like fMRI are helpful, but they don’t show the full picture. They can be hard to interpret, affected by small movements, and may not fully reflect what’s really happening in the brain.

-

It can lead to unfair labels: If we use brain scans to say teens are always emotional or not thinking clearly, we might underestimate their abilities or ignore their opinions. This can lead to unfair treatment and limit their chances to grow and learn.

Some researchers argue that the teenage brain is shaped by the life experiences and environments of teens, so just seeing a link between brain activity and behavior doesn’t prove one causes the other (Wright et al., 1999). The idea of neuro-realism means that people are more likely to believe a study if it includes brain scan images even if the study has problems (Gruber, 2017). Critics warn that brain development is a lifelong process. Our brains keep changing from childhood all the way into old age. New brain connections are always forming, and older ones are being removed (Baltes, Reuter-Lorenz & Rösler, 2006; Eisenberg, 1995). For example, research shows that the Corpus Callosum, the thick bundle of nerves that connects the left and right sides of the brain keeps growing even into adulthood (Pujol et al., 1993). One of the strongest criticisms of using brain science to explain adolescence is that scientists still cannot accurately predict how teens or adults will behave just by looking at brain activity.

For a long time, scientists have tried to explain group differences, like between teens and adults, or between males and females by pointing to the brain. This has often involved reinforcing stereotypes. Some brain researchers say that teen brains are immature because teens are more likely to take risks or act impulsively. They suggest that this risk-taking is a sign that teens are less developed or less capable than adults, and that this difference can be seen in the brain. About 30 years ago, another trait, youth violence, was also seen as a mainly teenage problem. Some lawmakers believed that violent teens had something wrong in their brains and wouldn’t change, so they pushed for harsh punishment (Dumit, 2014). Throughout the history of science, people have often accepted research findings simply because they confirm what society already believes. For example, claims that men have more brain areas for math have been popular because they match social stereotypes. Many people only trust findings about behavior if they can be shown in the brain, even though brain scan data (like fMRI) is complicated and often debated. Experts say that brain data should be backed up by other sources to be trustworthy (Racine et al., 2005).

When the brain is looked at in isolation and divorced from the social, political, and historical context, any finding is automatically ascribed to the neurological makeup of the individual and therefore considered biological (Harding, 2016). Let’s look at the finding that adolescents and adults tend to ascribe different emotions to the same face, anger and fear respectively. There are several problems with the conclusion that the authors draw. They do not discuss intra-group differences. In other words, how did brain functioning within the two groups (adolescents and adults) affect responses? Did the adults in the sample whose amygdala was active misinterpret facial expressions? For a theory to be substantiated, it is not enough for there to be broad group differences, but the theory must be able to explain individual differences. Secondly, expressing and judging emotions is also laden with social significance. How emotions are identified and responded to depends on the social status of the people who are attempting to communicate to each other. For teens, their conclusions about adults’ emotions are based on their experiences with significant adults around them.

Adults hold a great deal of power, especially over teenagers. When they feel fear, whether for the youth under their care, or for their own safety, it often comes out as anger. For example, when my husband and I punished our son for driving recklessly, he responded bitterly, accusing us of taking the car away just because we were angry. We tried to explain that we were actually scared for his safety. This kind of misunderstanding is common in relationships where there’s a power imbalance. People often misread each other’s emotions, and these mis-readings aren’t always about brain differences. Research shows that behavior is shaped by many influences beyond biology. One study, for instance, found that people with insomnia often misinterpret emotions because they don’t scan both the eyes and mouth at the same time, something non-insomniacs usually do. While biology plays a role in adolescent behavior, it’s only one part of a much larger picture. The brain, hormones, and neurochemicals are all shaped by environmental factors as well.

Thus, as critics of brain research point out, perceived and stereotypical behavioral differences between adolescents and adults are automatically ascribed to brain differences in structure and function; other social, political, economic, and familial factors are underemphasized by biological researchers. Good scientific methodology requires that researchers have a hypothesis backed by theory before they begin their study; brain research exploring group differences often ends up being a fishing expedition for patterns that reflect prevailing views about the groups. Data from fMRI studies, impressive as they may look, are a result of complex data analysis and processing, and only as good as the objectivity of the researchers who conduct the study. There are drawbacks with using the fMRI as a standalone measure of brain activity. Some researchers recommend triangulating the results with other ways of obtaining brain information that rule out researcher bias and methodological errors (Eklund, Nichols & Knutson, 2016). There is evidence, for instance, that the same areas are activated when very different stimuli are presented, or where different outcomes, i.e., pleasure or fear, are expected from the participants (Hommer et al., 2003).

One concern that critics have raised is that brain scans can’t reliably predict how someone will behave (Helfinstein & Casey, 2015). For example, you can’t look at a teenager’s brain and know if they’ll be impulsive or take risky actions unless the case is very extreme (Rosenberg, Casey & Holmes, 2018). Most people fall within a normal range of behavior, so predictions based on brain structure aren’t very accurate. Also, the emotional situation matters a lot. Teens are more likely to act impulsively in emotionally intense situations. So, it’s hard to say that a person’s behavior is caused just by how their brain is wired. In many cases, the brain itself is shaped by the environment and experiences a person has (Bettencourt, 2017).

Review and Reflect

REVIEW

- What are the areas in the brain that change during puberty?

- How does an adolescent’s environment impact their behavioral patterns?

- What are some strengths and drawbacks with understanding adolescence from a biological framework?

REFLECT

- How would you describe your emotional patterns as an adolescent? Have your emotions changed? If so, in what ways are your emotions different?

- What was your environment like growing up? How were you influenced by your cultural and social context?

Psychological Perspectives of Adolescence

Psychological views of adolescence generally align with biological views. Both see adolescence as a universal, biologically based stage of life marked by major changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior. They also share the belief that human development happens in clear, separate stages, from being immature and not fully developed to becoming more mature and fully formed. This way of understanding adolescence has shaped how most experts think about teenagers. Because psychological theories have had a big influence on how we think about and make policies for adolescents, it’s important to look at how these ideas developed and what schools of thought they come from.

Stanley Hall is often credited with introducing the term adolescence. In 1904, he published a book in which he described adolescence as a time of “storm and stress.” Influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, Hall believed that just as species evolve, individuals also go through stages of development. He argued that the emotional ups and downs of the teen years are natural and even necessary to shape a stable adult personality (Singer, 2017).

The Psychoanalysts

Erikson’s Stage Theory of the Lifespan

Erikson conceived of development as lasting through the entire lifespan; however, the issues and dilemmas facing individuals varies based on one’s age and culturally appropriate tasks for that age. In adolescence, the search for identity dominates youth attention.

Psychoanalysts, starting with Sigmund Freud, built on the idea of life stages by outlining a developmental path from birth to adolescence. Freud proposed five stages of childhood, each focused on sexual or pseudo-sexual feelings tied to different areas of the body, ultimately leading to heterosexual attraction in adolescence (Freud & Bonaparte, 1954). His theory reflects a clear heteronormative bias. Freud also introduced the idea of individuation, the process of separating from one’s parents, as a key task of adolescence (Freud, 2018). His daughter, Anna Freud, emphasized the role of sexuality in adolescent development, arguing that teens often behave in contradictory and unpredictable ways due to emerging sexual needs. She described adolescents as torn between extremes: selfishness and generosity, social belonging and solitude, optimism and pessimism, laziness and ambition. According to her, it is normal for teens to temporarily regress to earlier stages of development, letting their desires dominate their behavior (Freud, 1946).

One of Freud’s most prominent students was Erik Erikson. Like Freud, Erikson believed that there are certain universal, inherent, age-related needs that all humans share no matter where they live or how they live. However, unlike Freud, Erik Erikson underemphasized instinctual needs like sexuality and aggression; he spoke about the importance of our conscious thoughts and decision-making skills (Erikson & Erikson, 1998). Erikson conceived of development as lasting through the entire lifespan; however, the issues and dilemmas facing individuals varies based on one’s age and culturally appropriate tasks for that age. During adolescence, the biggest challenges facing individuals revolve around an appropriate defining of one’s identity, these include choosing one’s values, beliefs, career paths, life goals and life mission. The decisions individuals make during these years can affect the rest of their lives (Erikson, 1994).

Erikson’s students built on his work and identified four common ways that adolescents respond to the challenge of figuring out who they are. Two of these responses are considered healthy: identity formation, where teens make thoughtful decisions based on their own values and needs, and identity moratorium, where they continue exploring and questioning before committing to a clear identity. Less healthy responses include identity foreclosure, where teens adopt identities based on their family’s expectations rather than their own choices, and identity diffusion, where they feel confused or overwhelmed and stop trying to define themselves. Identity diffusion and role confusion can sometimes lead to harmful or self-destructive behavior (Marcia, 1966).

The Cognitive View of Youth

Jean Piaget, a highly influential psychologist, significantly shaped how we think about adolescence, especially in education. Like Freud and Erikson, Piaget believed children develop through universal stages from infancy to adolescence (Labinowicz, 1966). While Freud and Erikson focused on emotional development, Piaget studied how children’s thinking, particularly logical reasoning develops over time.

Piaget believed that children are born with an instinct to organize their experiences into mental frameworks, or schemas, which evolve as they interact with their environment. He outlined four stages of cognitive development:

-

Sensorimotor Stage (birth–2 years): Infants learn through physical interaction with the world. They lack object permanence, the understanding that things still exist even when out of sight until around 18 months.

-

Preoperational Stage (2–7 years): Children begin to use language and symbols to represent experiences. However, their thinking is still dominated by perception and lacks logical structure.

-

Concrete Operational Stage (7–12 years): Children develop logical thinking but are limited to concrete, tangible situations. They can classify objects, arrange them in order (seriation), and understand conservation, that quantity remains the same despite changes in shape or appearance.

-

Formal Operational Stage (12 years and up): In adolescence, abstract and hypothetical thinking becomes possible. Teens begin to use propositional logic, understand concepts like truth and justice, and are able to form theories by synthesizing information (Inhelder & Piaget, 2013).

Piaget viewed the abstract thinking that emerges in adolescence as the highest form of human reasoning. He and his followers emphasized that teenagers are capable of thinking about complex moral issues, such as truth and justice. They can imagine an ideal, fair world and are often motivated to take action to help create that world. Historically, young people have often led social justice movements, especially when older generations have accepted inequality as long as it doesn’t affect them directly. Research by Piaget and his students found that adolescents often score higher on moral reasoning than adults (Kramer, 1983). By age 12 and beyond, young people can also think scientifically, controlling variables, testing hypotheses, and drawing logical conclusions. This kind of thinking is used in scientific experiments and requires combinatorial logic, or the ability to systematically generate and consider all possible combinations of a set of factors (Bart, 1971).

Piaget’s theory has faced several criticisms. Some studies have shown that children can complete Piagetian tasks at much younger ages than he proposed, especially when the tasks are made more familiar or relevant to their everyday experiences (Myers & Ahmed, 2016). Other researchers have questioned the idea that Piaget’s stages are universal. They argue that factors such as culture, gender, and ethnicity play a significant role in how cognitive abilities develop. In particular, critics point out that Piaget’s stage sequence often does not hold up in cultures where Western-style education is limited or absent (Brubaker, 2016; Perrucci, 2017). To his credit, Piaget remained an active researcher and writer into his later years and welcomed critical engagement with his work.

Ecological Theories

Throughout much of the 20th century, biological and psychological theories of adolescence have held sway over social policy, education, and parenting practices. Educators and parents alike were encouraged to align their methods with the developmental stages, biological, emotional, and cognitive, articulated by theorists such as Piaget (Furth, 1970). A prevailing consensus among child development experts maintained that children progressed from undifferentiated behaviors to increasingly sophisticated forms of thought, with these transformations understood to follow a biologically timed sequence of brain and bodily maturation. While some theorists nominally acknowledged the role of social influences, such factors were largely peripheral and seen as having little bearing on the core developmental trajectory. Human development, in this framework, was presumed to follow a universal, context-independent path, with any deviations from this norm dismissed as anomalies or errors (Ertem, 2017; Boss, 2016).

A new generation of researchers began to challenge the idea that child development is the same across all contexts. One of the most influential voices in this movement was Uri Bronfenbrenner, who proposed that development is shaped by a complex system of relationships and environments. He introduced the Ecological Systems Theory, a dynamic model made up of concentric circles, each representing a different layer of influence on the child’s growth:

-

Individual: At the center are the child’s inborn traits such as temperament, genetic predispositions, and physical features.

-

Microsystem: This includes the child’s immediate environments where direct interaction occurs, such as the family, school, peer group, and neighborhood.

-

Mesosystem: This layer describes the interconnections between different parts of the microsystem; for example, the relationship between a child’s parents and teachers, or between home life and school experiences. These connections can be either supportive or conflicting.

-

Exosystem: These are external environments that indirectly affect the child, even though the child is not directly involved in them. Examples include a parent’s workplace, local government decisions, or community health services.

-

Macrosystem: This is the outermost layer, encompassing the broader cultural values, laws, customs, and ideologies that shape all the inner systems. It includes social norms about education, gender roles, economic policies, and other large-scale influences.

-

Chronosystem (added later): This dimension accounts for the role of time in development, both in terms of a child’s personal timeline (e.g., the impact of parental divorce or the COVID-19 pandemic at a particular age) and historical time (e.g., growing up in a time of war or rapid technological change).

Bronfenbrenner’s theory helped shift the focus from the child as an isolated individual to a view of development as deeply embedded in and shaped by a web of social, cultural, and environmental contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 2009; Kochtitzky & Cracchiola, 2016).

Here are concrete examples for each layer of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, showing how different environments influence a child’s development:

Individual: The child’s own biological and psychological traits such as a naturally shy temperament, a child born with a learning disability, having high energy levels or a strong memory, children’s physical health or chronic illness.

(Courtesy Kochtitzky & Cracchiola, 2016)

A Dialectical Materialist Psychology:

While Piaget was developing a psychology of children’s development based on the growth of their logical and conceptual ‘abilities’, a parallel psychology was being developed in the Soviet Union based on children’s lives as it intertwines with the material, social, economic and political world in which they are raised in. While Bronfenbrenner theorized that children were influenced by the many circles of influence them, Soviet psychologists proposed that the very trajectory of childhood is determined by how history and the socio-economic systems led up to the moment. In their view, the elements of what constitutes the individual is related to the context, in influenced by the context and changes the context in turn. This complex relationship is dialectically related but unlike Piaget’s theory, the source of the change is the material and social context. Thus, material history pervades every sphere of the child’s life provides . The cognitive psychologist who probably is most closely aligned with historical dialectical materialism is Lev Vygotsky (1896- 1934) who in his short life transformed how cognitivists and educational practitioners viewed learning and development (Rattner & Silva, 2017). Today, however, few western educational experts recognize his theory as being influenced by HDM (principally Vladimir Lenin), even though along with Jean Piaget, his works form the fundamental basis of educational praxis in Europe and North America. Vygotsky grew up in Tsarist Russia and as a person of Jewish origin, witnessed first-hand the discriminations and biases faced by national minoritized communities under a dictatorial monarchy. He was a brilliant student; however, many opportunities were closed off for him because of the antisemitism under Tsar Nicholas. Admission to university was limited for Jewish students, who were mostly chosen via lottery. It was good fortune for the world therefore that he was able to find a place in Moscow University right before the Bolshevik revolution (Yasnitsky, 2018). Vygotsky was deeply influenced by the writings of Marx, Engels, and Lenin and much of his work as a learning theorist was inspired by Marx’s framework for understanding exploitation and the liberatory engagement of the oppressed (Au, 2007b; Packer, 2008). The first translations of Vygotsky’s work appeared in the west in the 1960s, and by then there was such anti-Marx fervor that all his references to Marx or Lenin were deliberately removed by the translators (Kozulin, 1986; Vygotsky, 1962)

There are enormous parallels between Vladimir Lenin’s work on imperialism and the famous learning theorist Lev Vygotsky’s work in the area of education on how children learn. Vygotsky was a Soviet psychologist who is now very popular in educational circles all over the world. When his works were first translated into English, all references to Marxism were left out because the authors decided this would make his work less palatable to western readers. In fact, much of Vygotsky’s learning theory was based on Lenin’s writings and today there is a rediscovery of the connections by academics. Vladimir Lenin was the leader of the Bolsheviks who overthrew the Czar in Russia in 1917. He was also a prolific writer even as he was organizing workers and peasants in Russia. So, much of his own theory on working class consciousness was based on his own experiences. He proposed that workers who are routinely exploited under capitalism develop a spontaneous knowledge about their exploitation and suffering. They are able to articulate all the ways in which their lives are unstable, but they are not able to put it all together in a way that promotes social change; that requires collective action. The work of an educator/organizer is to develop that into a scientific understanding of their lives. Vygotsky similarly spoke about how children have a spontaneous understanding of how the world works around them; the role of the educator is to be sensitive to where the child is at and move them to a more advanced understanding of the world. A teacher has to stay within the zone where the child can do a level of work on their own and the level where they require the help of an advanced leader/teacher/collective to complete the task.

For Lenin the zone consisted of the level where workers just being angry, agitated and uncoordinated in their response and a higher level where their consciousness was now social and collective (radical subjectivity) and where everyone in a movement shared a consensus on systemic problems that resulted in their plight and how to move forward in the movement. For both Vygotsky and Lenin consciousness and knowledge building is always a social collective enterprise and there is no such thing as individual emancipation or individual knowledge that is unmoored from society-group. If a leader or educator introduced concepts too early or urged action prematurely (adventurism such as individual vigilante violence) both the movement and learning are set back. If the leader delayed learning and action (opportunism by making small changes that don’t affect the real goal of a workers’ state), collective consciousness withers away. If you’ve watched the movie Joker, you will see an example of spontaneous anger that is not moored in proper consciousness. Joker is abused by society, and he engages in undisciplined rioting and destruction. In a proper movement, the consciousness of the workers is aligned with the larger goals of the group, thereby ensuring a change in social order and thinking.

Marx had proposed that all successful struggles were based on class solidarity and not ideological solidarities (such as race and gender). He reasoned that ultimately how humans interact with this world is material; humans have always worked to bring nature under control to suit their needs and all social formations, past and present, were designed to aid this process. This process of working as a group to aid in survival may be based on gender or race, but they are biproducts and therefore their meanings are always in flux throughout history. Social class, however, is rooted in the material engagement of a community with the world and therefore most social change has to begin there. As an illustration, in hunting gathering communities there was enormous gender equity because the mode of production did not lead to a lot of surpluses (savings) by the community; so, there was nothing to protect. With the coming of agriculture, feudalism became the social arrangement to mediate work, leading to increased land, grain surpluses and things that needed protection; there were a group of people who became more powerful, and women now were considered inferior and their sexuality had to be controlled so the land and property remained within the family or clan. Similarly, under capitalism, racism and slavery became a way to increase capitalist profits. Thus, the social formation and its associated class structures undergird all other exploitations. In Au’s conception, “In the most general sense, to be “conscious” in Lenin’s terms means to be thought-out, planned, self-aware, and using systematic analysis to develop strategy and act as part of a larger working-class movement against a system that is not operating in the interests of workers.” For Lenin, and Vygotsky, the ultimate teacher is a solidarity party that guides and directs its leaders to engage with the masses to bring about change, while at the same time, improving and clarifying the changing social circumstances on the ground. In the Russian case, it was the Bolshevik communist party that formed the highest level of consciousness and knowledge production. In China, it was the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)

According to Lenin the political workers party leadership ought to be totally dedicated to both growing their own knowledge of the contradictions of the society they live within, in the company of their fellow leaders while at the same time engaging in teaching and educating the masses about how their personal life is related to the larger struggle. That is one reason why, most revolutionaries after they take over the power of the bourgeois (capitalist) state, enact mass political education for the masses. As more workers advance along the Zone of Proximal Development, they can do the leadership work themselves. Xi Xing Ping, the current premier of China was one of those youth. He came from a privileged family and was sent to a village for most of his youth to learn about the struggles of peasants. He also failed his communist party entrance exams several times before passing the exam. You see how the idea of Lenin’s idea of social transformation works on a social and national scale. Both theory and Practice are central to knowledge development

Vygotsky proposed that like physical tools used by humans to mediate their relationships with nature, thought and mental symbols are instruments that society devised to mediate and negotiate human functioning within the natural world. Initially, actions by infants are disconnected from their thinking; however, actions increasingly lead to sophisticated thinking and symbol formations leading the two processes to align, but always these cognitive processes are dialectically related to the material contexts of existence. Teaching is therefore always flexible and contingent on the learner and the context. For Vygotsky, language was the most important tool of them all and the way in which language is conceived and used is mediated by society. He criticized Piaget’s theory of universal stages and countered that in fact learning with an expert adult can influence the course and rate of development of children’s cognition. Vygotsky in his own cross-cultural work found that all societies have devised unique ways of teaching their young and the tools that they would need to adapt to their environment (Vygotsky, 1978; 1980).

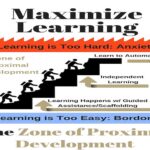

One of the central concepts introduced by Vygotsky is the Zone of Proximal Development. The concept of the ZPD is borrowed from Marx’s pedagogical ideas of inquiry and presentation and Lenin’s ideas regarding the need for flexibility of the workers movements in terms of strategies but not of its principal. Vygotsky defines the difference between the levels of performance when a novice does a task by themselves and their level of achievement when they can do the same task with an expert guiding them. For him, a good teacher is one who stays within the zone and leads the child to increasing proficiency in a task. The most effective way to enable children to learn a skill and to problem-solve is to constantly introduce them to a task that they may not be able to do by themselves but can do with the help of an expert. The expert will find that children are performing increasingly complex tasks that they may not have been able to perform if they were left to learn for themselves. Thus, Vygotsky differs from Piaget in the importance that he attaches to language and the role of expert adults in learning and development (CPD, 1979; Vygotsky, 1978; Parameswaran, 1994). Vygotsky died at a relatively young age and his work was rediscovered in the west in the 1960s when some of his seminal writings were published in English. Piaget read some of his writings and expressed great appreciation for the unique insights that Vygotsky provided (Parameswaran, 2006).

Review and Reflect:

REVIEW

1.What are some ways adolescents can respond to an identity crisis?

2.What is the Zone of Proximal development?

REFLECT

1.How did your experiences in and out of school have an impact on your identity?

2.How can you use the cognitive/ecological theories to better respond to youth’s needs?

Recent Critical Perspectives on Adolescence

Contemporary Perspectives

The theories about adolescence discussed earlier, focused their inquiry on organismic, bodily changes that occur in adolescence to a greater or lesser extent. Thus, the biological theories of adolescence explored brain and hormonal changes in the body while the psychological theories focused on the consequences of bodily changes during adolescence on the behaviors of individuals. The following sections of the chapter outline more recent discussions about “adolescence” that center on its social construction and its historical specificity. Many of the new schools of thought about youth were a direct critique of the psychological and biological view of teenagers.

Historical Perspectives of Adolescence

The lives of youth have varied enormously historically in the US and in other cultures. A historical exploration of the written records of the early Puritans in New England reveals that there was very little distinction made between children and youth at that time. A 10-year-old and a 17-year-old were both perceived very similarly in terms of their maturity during the early colonial period in the USA; they often studied together, played together and performed household duties side by side (Mintz, 2004). There were strong relations of dependence between adults and children living within families; even when children worked away from home, their earnings were sent home as supplemental income. Most middle-class youth were sent to work under master craftsmen as apprentices. The masters treated them like they treated their own children. Later during the early industrial era, as many of these masters’ establishments turned to factories, there was mass exploitation of young people where the masters refused to train them completely but would make them work on one part of the creative process. Slave children could do minor work until age 14 after which their responsibilities towards their masters increased dramatically and they were exploited with little regard for their welfare.

The industrial revolution brought enormous changes to the American population. Young men and women were employed in large numbers in factories where they spent time together for extended periods of time away from family control. Their lives were hard, and they often had to work for over 13 hours a day (Humphries, 2010). In 1846, the Irish potato famine brought in a flood of immigrants into the USA. Several of the large northeastern cities were more than a quarter filled with immigrant population. The new immigrants were poor and, more importantly, culturally different from the earlier immigrants. Cities had high concentrations of youth who visibly posed a threat to the elite families who in turn attempted to move and live further away from poor immigrant communities (Katz & Davey, 1978).

In the 19th century, well-to-do families began supporting high schools to isolate their teens from children of immigrants, street kids, vagrants and deviants (Katz, 1976). However, schools were still not the normal experience for most children until the Great Depression. The idea of ‘Education for all’, did not take place until World War II (Savage, 2008). Initially, girls were sent to school at greater frequency than boys because it was looked at as a route to a teaching career; also, within families, boys’ income was less dispensable than girls. For a while, schools and colleges existed side-by-side and as alternatives for students. The most popular colleges were the ones teaching agriculture because the population was still predominantly rural. As colleges began to be perceived as being more useful than high schools, the latter became feeders for colleges (Hine, 2000).

In the late 1800s, high schools became places to train children in nationalism and patriotism. As the communist movements took hold among people around the globe, high schools became spaces to train students to resist it. Initially, as child advocates demanded better access to public schools, industry leaders resisted those calls because of their need for cheap labor (Hine, 2000). However, as machines took over human functions more and more in factories and the need for workers shrank, industrialists warmed up to the idea of high schools to avoid rioting and other antisocial behavior on the streets. After the crash of 1929 when joblessness among adults was rampant, youth labor reforms gained a foothold in society (Sommerville, 1990).

Several social reform measures in the early 1900s changed the scenario for youth, labor and schooling dramatically. The Juvenile Justice System now took over the role of disciplining, which parents and families were typically responsible for (Empey, Stafford and Hay, 1982). The method of justice within the system was arbitrary and mimicked middle-class parenting styles. The laws surrounding youth sexuality became increasingly rigid. The minimum age that youth could have sex was raised to 18, with a special eye towards curtailing girls’ sexual activity (Champion, 2001).

It was not until the Depression years of the 1930s when adolescence was codified and regimented by the government. As large numbers of workers became unemployed, the government passed laws that prevented people below the age of 18 to seek work. The New Deal prioritized work for the adult male members of households so families can tide over the difficult times. This resulted in large numbers of youth enrolling in high schools for the first time where they spent enormous amounts of time with other people their own age. The word teenager was coined around World War II, signifying all that it means today for us (Medovoi, 2005). As adults went off to war, teenagers got back the jobs that they had lost during the great depression – and more. They were making as much money as adults were because of great shortages in the workforce. Most youth, however, chose to stay in schools because of laws that deferred military service for students enrolled in high schools. Thus, youth were isolated from adults and they had a lot of spending money – the two elements that gave birth to the modern youth culture (Hine, 2000).

The post-war prosperity, the universalization of high school and Hollywood narratives later dramatically spread the experience of adolescence for youth around the country. Teenage hood became synonymous with youth subcultures, fashion trends and innovation in music, dance and the arts. As historians note, five decades ago there were no clearly identified cliques among teens; today, from the kinds of clothes worn to music listened to, teenagers are defined by their groups (Rotundo, 1993). There are still youth left out of the teen experience as we now know it – immigrant and ethnic minority youth, sexual minorities and lower-class youth experience very different ‘adolescence’ as compared to white middle- and upper-class youth. In the 1990s, several legislations were passed ostensibly aimed at protecting poor and minority youth, but they ended up being exceedingly punitive and restrictive; the hysteria generated by adult fear of youth affects disadvantaged teens much more than they do middle-class adolescents (Cohen, 1997).

Postmodernist Critiques

Some of the most profound critique of the psycho-biological frameworks of adolescence has come from the poststructuralists and postmodernists. They go beyond claims of historians that adolescence is a recent phenomenon to asserting that the language around adolescence and teenage hood arose from colonial science and has been used as a form of power to manage the population (Lesko, 2001). Some of their major thesis include:

Social-Darwinism and Colonialism: Darwin’s theory of evolution was reinterpreted by social scientists to justify the colonialist ambitions around the globe. Social science early on used his theory to classify cultures and communities from very primitive to the very advanced, with European white male society representing the very pinnacle of the realization of human possibilities (Paul, 2003). The project was extended to individual human lives by classifying people of different ages as being differentially advanced, moving from the savagery of children to the barbarism of adolescents and finally the civilized behavior of adults (Loomba, 2007).

Fear of Loss of European Masculinity: At a time when colonialism was being overthrown everywhere, a fear for the manliness of the European white male led policy makers to propose adolescence as the great turning point for individuals and societies; youth was the period when the greatest care had to be exhibited in grooming and training, so citizens can become productive and responsible towards the state (and in capitalist societies, to capital) (Moses & Stone, 2013).

Marking of Youth Bodies and Minds: In the last century there has been an intense effort to scrutinize, mark, label, measure and evaluate youth and young adults for signs of deviance. Normal standards of behavior were established through studying and analyzing youth bodies and behavior that was highly gendered and racialized. These norms ignored the specific social and cultural contexts in which people lived in (Saltman, 2005).

Surveillance and the Panopticon: Like the panopticon prison (pictured to the right) where prisoners internalize prison regulations because of the mere ‘imagined’ gaze of a guard placed at the center of the prison, adolescents learn to regulate their behavior in accord with societal expectations (Foucault, 1979).![]()

Essentializing and Normalizing Adolescence: Certain stereotypical exhibited behaviors of young people are conceived of as intrinsic (essentialized) and popularized (normalized). The constant push to label makes it easier for teenage specialists to consume information about youth quickly and detect any deviation from the normal and thus to intervene in youth’s lives rapidly to enforce rules of normality (Raibble & Irizarry, 2010). Therefore, while much diagnosis and measurement around educational achievement is purported to be good for students, the real purpose is to reduce any variance from normal behavior.

Age-wise Classification: What followed were a series of steps to organize society in general and schools along ages, so both the administrator and the administered had a clear understanding about what was expected of them in terms of behavior, feelings and thinking.

High Schools as Training Spaces: High schools are particularly important settings to train youth in the external corporate culture that students will eventually be members of. Schools tend to be hierarchical with scarce rewards going to the children who buy into the system and whose families are privileged enough to be able to envision the possibilities that an unequal system offers their children (Willis, 2017). High schools are highly competitive, isolated from the outside community with an emphasis on role-oriented individual identity (Spring, 2005).

Prioritization of Future Over Present: Since early conceptions of adolescence is rooted in an ‘evolution theory’, the future is prioritized over the present; thus, teachers and policy makers grapple with shaping teenagers into compliant adults, over the fulfillment of the potential during the period of adolescence.

The history of adolescence demonstrates that it was conjured up within a historical time, space and context in order to serve functions that were and continue to be nationalistic, militaristic and anti-feminine. These conceptions according to postmodernists were further refined and solidified by disciplines like psychology, anthropology and criminal justice. Once the basic framework was laid down, the stereotypes and prejudices against youth were further ‘substantiated’ and popularized by the sciences. The consequence of an unexamined notion of adolescence today has been a view of adolescence that is race, class and gender based; thus, conceptions of maturity are Eurocentric, male-centered and biased towards the upper-class.

Sociological Perspectives

Since the 1960s, there have been a flood of ethnographic studies exploring adolescent lives in different contexts. They demonstrated convincingly that adolescents do not live uniform lives and in fact, sociologists term this period ‘Adolescences’ because of the vast differences in the experiences of youth based on gender, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, disabilities, religion and social class (Lesko, 1996). Of these, race and social class have been the most studied.

Social class has an enormous impact on teenage experience. Poor teens tend to be pushed out of school at higher rates, work full-time more often and have fewer resources when they attempt to advance their career aspirations. The digital divide between lower class and middle- and upper-class youth, white and minority youth has grown wider (Lareau, 2002). Youth of color experience a very different adolescence from white middle-class youth (Dubos, 2017). The former has fewer opportunities for advancement in schools, are discriminated against by institutions in society, tend more likely to live in poorer neighborhoods and are less likely to go on to higher education at lower levels. Both poor and minority youth have higher identification rates of physical and mental health issues, adding to the discrimination that they face from social institutions (Hogan, 2017).

Gender and its impact on youth lives has been widely explored; many writers have observed how girls’ self-esteems plummet when they move from elementary to middle school. Some have even called the phenomenon, the silencing of girls. While boys tend to get louder and more confident as they go through middle school, girls do not feel like they have the permission to voice their opinions (Arnett, 2014). This is especially true of white and Asian girls among whom passive femininity is valued. Individuals with various disabilities are increasingly labeled and isolated in schools leading to their exclusion from social cliques and groups in school (Rose, Simpson & Moss, 2015). Transition into adulthood is fraught with difficulties for many people with disabilities and they are offered few services to help them with finding employment (Wei et al., 2015). Many writers have documente

d how youth with disabilities are perceived to be asexual (Davis, 2016). With increased profiling of youth belonging to minority religions, people from these communities face harsh treatment in schools and in communal spaces. Youth from non-normative sexuality and gender groups have talked about their intense loneliness and confusion as they navigate adolescent issues. Unlike youth from other minority and disadvantaged groups, homosexual and transgender adolescents have few familial and community resources. It is no wonder they are represented disproportionately among those who drop out of school, commit suicide and abuse drugs and alcohol (Lucassen et al., 2017).

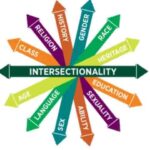

The experiences involved with “coming of age” among youth is different based on their family and individual group memberships. Their membership does not just influence their adolescent experiences but changes the very passage through this period for them – the age they enter adolescence, the dilemmas, challenges and the developmental goals they are confronted with, the support they receive and when they transition into adulthood. It may shorten or lengthen traditional adolescence and change their psychological and physical makeup as they go through teenage hood. All of these social and political factors based on one’s social identity have a combined and complex influence that is termed ‘intersectionality’ (NAIS, 2018).

Political Perspectives

Since the last 20 years, there has been a growing group of youth advocates and researchers who have claimed that adolescents are really an oppressed minority group that need to organize to demand their rightful place in society (Males, 1996). Political advocates of young people claim that as the proportion of children of color grew in the 1980s and 1990s, the white majority population responded with fear and loathing towards these youth. Lawmakers responded to white fears by cutting social services and safety nets for communities of color and for poor people the majority of whom are white. The result was that the poverty rate among children and adolescents grew even during the economic prosperity of the 1990s. Advocates argue that while adults (especially wealthy ones) are paying some of the lowest taxes in this country’s history, the proportions of children in poverty has grown (Males, 2015; Males & Brown, 2014).

There have been hysterical discussions about youth violence in the public sphere and demands for ever more stringent punishments against minor infractions, even as youth violence continued to drop (Schissel, 2016). There is evidence that when there is violence involving youth, it is often inflicted by adult members of a family against children and youth in the family. Youth on adult violence is less common than adult on youth aggression (Wekerle & Kerig, 2017). Instead of responding with social policies aimed at increasing communal harmony, mental health help and reducing poverty in communities, policy makers have responded to this dire situation in the living conditions of youth with force and punitive discipline like zero-tolerance in schools (Wilson, 2014).

The US has the highest rates of teenage pregnancy in the developed world. Again, the public discourse around this issue has been harsh, blaming teen girls for the situation. There is strong evidence that in more than 60 % of cases where teen girls get pregnant, adult men are the impregnators and yet there is silence around this latter issue (Delios, 1996). Similarly, teenagers form a miniscule fraction of the cases of drug overdose and drunken driving in communities. Yet, policy makers have imposed harsh penalties on children for minor infractions around possession of alcohol or drugs while they let privileged adults get away with repeated abuse of alcohol and drugs. According to Males (1998), aspirin is the most abused drug by teens and most often lands them in emergency rooms – and these are often given by parents or prescribed by family physicians. There is inherent racism and class oppression in the way public policy and perceptions are crafted towards young people. One example is the case study of public policy around the crack epidemic in the 1990s versus the opioid epidemic in the early decades of the 2000s. While the crack epidemic predominantly affected Black and brown communities, the opioid epidemic affects white communities. Victims of the crack-cocaine epidemic were criminalized and imprisoned in large numbers. Victims of the opioid crisis are looked at as mentally ill and needing therapeutic help. Even the way the public framed the problem (epidemic versus crisis) is tinged with differential judgement and values.

Over the last 40 years there has been a stripping away of youth rights, replaced by harsh conditions under which youth infractions will only tend to increase as abuse and other socially unacceptable behavior goes underground (Johnston et al., 2016). The irrational basis for juvenile curfews in the USA is one symptom of societies scapegoating youth. Resources for public schools and colleges have been whittled away and funding for prisons have increased proportionately. With economic strain, there are fewer jobs for young people and fewer community resources to keep them engaged (Mitchell, Leachman, Masterson, 2016). Youth advocates demand that teens should be given a voice in government including voting rights so they can influence their future (Merry & Schinkel, 2016). The political view maintains that youth are discriminated against like other minority groups, especially as the proportion of people of color have increased in the US.

Aesthetic/Literary Perspectives

Writers and artists have celebrated youth as a time of transitions, new beginnings, insights and lost loves. Many have captured the pain, alienation and insecurities that plague that time of life with vividness and sensitivity, in a manner that theories and abstractions cannot. Immigrant writers have written eloquently about growing up in America with its accompanying feelings of alienation, longing for a safe space where they will be accepted as one among others and some capture the sentiments around the “coming of age” experience and learning to live holistically with all of their different selves (Ames & Burcon, 2016). Adolescence has signified turning points and changed perspectives in US society and writers have recalled the struggles with family, friends and society during this time both with horror and longing (Cart, 2017).

Within the literary views of adolescence there are two different kinds of writings, depending on the readership – either adults or ‘young adult’ readers. Much of the writings aimed at youth themselves tend to reflect the challenges that the protagonists in the novels face and the final overcoming those challenges either by “coming of age” or a point in the story where an experience forces the protagonists to view their lives and challenges differently (Coats, 2010). The aim of most young adult literature aimed at young readers is to help “grow up” the adolescents themselves. The other stream of writing aimed at adults (with adolescent characters) tend to be a lot more realistic about the possibilities and limitations of adolescent experiences in pushing the protagonist towards a new direction of change. In keeping with the general ethos of the 20th century adolescence, books aimed at youth are future oriented while those about young people aimed at an adult audience are more likely to depict in a realistic fashion, the challenges that adolescents face. In addition, some writers suggest that the YA novel is a 20th century marketing phenomenon – in many countries YA novels are called “jeans prose” because of their emphasis on the material culture of adolescents (Cole, 2008).

Both adult literature with an adolescent character and adolescent literature share certain common features but often teen literature aimed at an adult readership focuses on Entwicklungsroman, where an adolescent protagonist grows but does not reach a new stage of development. On the other hand, Young adult literature read by teens emphasize the experience of Bildungsroman, where an adolescent reaches adulthood and where they gain new freedoms and responsibilities (Iverson, 2010). The majority of modern adolescent and YA novels has an Entwicklungsroman narrative because the adolescent has grown a little bit but never enough to qualify as an adult. Postmodern theorists would point to this as evidence of the surveillance and controlling nature of society’s conceptions of adolescence (Gruner, 2010).

One issue that is often under-explored in YA literature is the power inequities embedded in the very telling of youth stories. Young adult literature often tended to be gendered. The stories predominantly featured girls and women in the form of short stories in magazines because girls read a lot more than boys. The narratives depicted girls moving from gender-neutral childhoods to more feminized adulthoods. While the gendered nature of the narratives has changed in recent years, critics point out that growth is often used to communicate to adolescents that appropriate maturity requires coming to terms with inequity and lack of power. According to Trites (1998), “Power is everywhere in adolescent literature.” The various institutions that youth interact with serve to define adolescent powerlessness in YA literature. Often, the culmination of the novel results in adolescents learning that institutions are important and possess more power than individuals.

There is great discussion today about whether books are appropriate ways to reach adolescents because of all the technological innovations that have dramatically altered adolescents’ use of media. As several researchers have suggested, children learn to use the computer before they learn to read. This has forced publishers and authors to be creative about coming up with interesting material for teenagers. Young adult fiction has become more edgy, hard-hitting and today explores profound issues like rape, sexual abuse, racism, gender discrimination (Behrman, 2006).

Conclusion

In conclusion, as this brief introduction to adolescence demonstrates, researchers and advocates differ widely in their thoughts on the phase of life that is commonly referred to as adolescence or teenage-hood or youth. The most profound difference lies in whether researchers view it as biologically created or socially constructed. Thus biologists, brain scientists and psychologists view adolescence as a natural phase of life with its specific universal traits and essential behaviors. Sociologists, anthropologists and historians dispute that adolescence is characterized by universal characteristics and point to cultural and social differences in what constitutes adolescence. Postmodernists extend that argument further by pointing out that all social phenomena are constructed and overarching theories often a creation of specific historical needs and become self-fulfilling. Political theorists argue for thinking of adolescents as an oppressed group while literature often reflects prevailing views of the society that adolescents live in. These varied conceptions have had an immense impact on how experts think about youth problems, strengths and the solutions to the problems.

Review and Reflect

REVIEW

1.What changes did the industrial revolution bring to the life of teens? How did this spark the beginning of teen culture in the US?

2.How has Hollywood shaped ideas about adolescence?

REFLECT

1.What social concepts or influences affected your adolescence? In what ways do social influences still impact your life?

Glossary of Terms

androgens

anna Freud

Bronfenbrenner

concrete operational stage

Darwin’s theory

depression era

digital divide

dopamine

dual systems model

entwicklungsroman

Erik Erikson

estrogen

exosystem

formal operational stage

industrial revolution

intersectionality

Jean Piaget

Lev Vygotsky

macrosystem

mesosystem

microsystem

nationalism

neurorealism

panopticon

patriotism

preoperational stage

progesterone

pruning

psychoanalysis

puritans

sensorimotor stage

serotonin

Sigmund Freud

social Darwinism

Stanley hall

testosterone

zone of proximal development

References

Ames, M., & Burcon, S. (2016). Reading Between the Lines: The Lessons Adolescent Girls Learn Through Popular Young Adult Literature. In How Pop Culture Shapes the Stages of a Woman’s Life (pp. 32-57). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Adolescence and emerging adulthood. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Baltes, P. B., Reuter-Lorenz, P. A., & Rösler, F. (Eds.). (2006). Lifespan development and the brain: The perspective of biocultural co-constructivism. Cambridge University Press.

Bart, W. M. (1971). A generalization of Piaget’s logical-mathematical model for the stage of formal operations. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 8(4), 539-553.

Behrman, E. H. (2006). Teaching about language, power, and text: A review of classroom practices that support critical literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49(6), 490-498.

Bettencourt, K. (2017). Adolescent Risk Behavior and Experiences with Flow (Doctoral dissertation, William James College).

Boss, P. (2016). The context and process of theory development: The story of ambiguous loss. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(3), 269-286.

Brubaker, J. (2016). Cognitive Development Theory. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies.

Cart, M. (2017). Young adult literature: From romance to realism. American Library Association.

Casey, B. J. (2015). Beyond simple models of self-control to circuit-based accounts of adolescent behavior. Annual review of psychology, 66, 295-319.

Champion, D. J. (2001). The juvenile justice system: Delinquency, processing, and the law. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Charlesworth, W. R. (1992). Darwin and developmental psychology: Past and present. Developmental psychology, 28(1), 5.

Chumlea, W. C., Schubert, C. M., Roche, A. F., Kulin, H. E., Lee, P. A., Himes, J. H., & Sun, S. S. (2003). Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics, 111(1), 110-113.

Coats, K. (2010). Young adult literature. Handbook of research on children’s and young adult literature, 315.

Cole, P. B. (2008). Young adult literature in the 21st century.

Crone, E. A., & Elzinga, B. M. (2015). Changing brains: how longitudinal functional magnetic resonance imaging studies can inform us about cognitive and social‐affective growth trajectories. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 6(1), 53-63.

CPD. (1979). LS Vygotsky: Mind in Society. The Development of Higher Psychological Processes.

Davis, L. J. (2016). The disability studies reader. Routledge.

Delios, H. (1996). Older men who targeted teens targeted. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1996-03-07/news/9603070071_1_teen-pregnancy-statutory-rape-laws-teenage-pregnancy

Donhauser, P. W., Rösch, A. G., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2015). The implicit need for power predicts recognition speed for dynamic changes in facial expressions of emotion. Motivation and Emotion, 39(5), 714-721.

Dubos, R. (2017). Social capital: Theory and research. Routledge

Dumit, J. (2014). 14 How (Not) to Do Things with Brain Images. Representation in Scientific Practice Revisited, 291.

Eklund, A., Nichols, T. E., & Knutsson, H. (2016). Cluster failure: why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(28), 7900-7905.

Empey, L. T., Stafford, M. C., & Hay, C. H. (1982). American delinquency: Its meaning and construction. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1994). Identity: Youth and crisis (No. 7). WW Norton & Company.

Ertem, I. O. (2017). The international Guide for Monitoring Child Development: enabling individualised interventions.

Eveleth, P. B. (2017). Timing of menarche: secular trend and population differences. In School-age pregnancy and parenthood (pp. 39-52). Routledge.

Freud, A. (1946). The psycho-analytical treatment of children.

Freud, A. (2018). Normality and pathology in childhood: Assessments of development. Routledge.

Furth, H. G. (1970). Piaget for teachers. Prentice Hall.

Goodenough, O. R., & Freeman, M. (2017). Introduction. In Law, Mind and Brain (pp. 15-18). Routledge.

Gruber, D. R. (2017). Three Forms of Neurorealism: Explaining the Persistence of the “Uncritically Real” in Popular Neuroscience News. Written Communication, 34(2), 189-223.

Gruner, E. R. (2010). Telling Old Tales Newly: Intertextuality in Young Adult Fiction for Girls.

Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence (Vols. 1 & 2). New York: Appleton.

Hall, G. S. (1916). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion and education (Vol. 2). D. Appleton.

Harding, S. (2016). Whose science? Whose knowledge?: Thinking from women’s lives. Cornell University Press.

Helfinstein, S. M., & Casey, B. J. (2014). Commentary on Spielberg at al.,“Exciting fear in adolescence: Does pubertal development alter threat processing?”. brain, 38, 329-337.

Hogan, D. (2017). Education and class formation:: the peculiarities of the Americans. In Cultural and economic reproduction in education (pp. 32-78). Routledge.

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (2013). The early growth of logic in the child: Classification and seriation. Routledge.

Iversen, A. T. (2010). Change and continuity: the Bildungsroman in English.

Janssens, A., Van Den Noortgate, W., Goossens, L., Verschueren, K., Colpin, H., De Laet, S., … & Van Leeuwen, K. (2015). Externalizing problem behavior in adolescence: Dopaminergic genes in interaction with peer acceptance and rejection. Journal of youth and adolescence, 44(7), 1441-1456.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Miech, R. A. (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19-55.

Hine, T. (2000). The rise and fall of the American teenager. Harper Collins.

Humphries, J. (2010). Childhood and child labour in the British industrial revolution. Cambridge University Press.

Katz, M. B. (1976). The origins of public education: A reassessment. History of Education Quarterly, 16(4), 381-407.

Katz, M. B., & Davey, I. E. (1978). Youth and early industrialization in a Canadian city. American Journal of Sociology, 84, S81-S119.

Kochtitzky, Christopher & Cracchiola, Michele. (2016). Built Environments for Improving Human Development and Promoting Health and Quality of Life. 10.1007/978-3-319-18096-0_32.

Kramer, D. A. (1983). Post-formal operations? A need for further conceptualization. Human Development, 26(2), 91-105

Labinowicz, E. (1980). The Piaget primer: Thinking, learning, teaching. Addison-Wesley Longman.

Lareau, A. (2002). Invisible inequality: Social class and childrearing in black families and white families. American sociological review, 747-776.

Loomba, A. (2007). Colonialism/postcolonialism. Routledge.